Welcome, listeners, to another episode of vted Reads: talking about books by, for, and with Vermont educators. In this episode… we own an oversight.

On this show, we are dedicated to breaking down systems of inequity in education. We administer flying kicks to the forehead of intersectional oppression! But we haven’t yet talked about disability.

So in this episode, we fix that, as we chat with Dr. Winnie Looby, who coordinates the graduate certificate in disability studies at the University of Vermont. Dr. Looby also identifies as a person with a disability, which is important, listeners, because the rallying cry of disability advocacy has long been “Nothing about us, without us.”

So we’re here, we’re clear, and we’re talking about “Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice,” by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha. Let’s limber up those kicking legs, folks, and talk about how disability too, is an equity issue.

I’m Jeanie Phillips, and this is Vermont Ed Reads. Let’s chat.

Jeanie: Hi, I’m Jeanie Phillips, and welcome to #vted Reads. We’re here to talk books for educators by educators and with educators. Today I’m with Dr. Winnie Looby. And we’ll be talking about Care Work, Dreaming Disability Justice by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha. Thanks for joining me Winnie, tell us a little bit about who you are and what you do.

Winnie: Yes, so my primary function, I guess is I work at UVM as a lecturer in disability studies, and also in foundations. And then I’m a coordinator for a program under the Center on Disability and Community Inclusion. And I’ve been working there for about four or five years.

Jeanie: And so excited to have you with us to talk about this subject. One of the things I’ve become aware of recently, is these two schools of thought about how we talk about people with disabilities or disabled people, do we use identity first language, like, disabled person? Or do we use people first language like people with disabilities? And I wondered if you had any thoughts about that?

Winnie: Yeah I think, from what I’ve absorbed, I think it’s kind of context specific. Say, if you’re talking to an individual who chooses to identify as an autistic person, that’s the language you use when you’re talking with them. But say, if you’re talking to a government official, or somebody else like that, the politically correct thing to say now is person with a disability. So that’s the language that you would use. But then say, if you’re within an activist circle, you might say disabled people disabled person. So it really kind of requires us to be deep listeners um to figure out what exactly might be the appropriate thing to say in that moment.

Jeanie: I really appreciate something I’ve heard from other people I’ve had on the podcast as well. This like ask people ask people how they want to be referred to. And I think we had Judy Dow who’s in an Abenaki scholar on and she said, you know, we talked about do people who want to be referred to as indigenous or Native American or Indian or, and she said, ask them, and think about tribal affiliations and things like that, as well. And so it’s really helpful for you to frame that, again, ask people how they want to be referred to. Thank you for that. So this book, and so our author frames, access, disability access, in this way, “access as service begrudgingly offered to disabled people by non disabled people who feel grumpy about it.” And she wants us to shift to a different definition of of access to “access as a collective joy and offering we can give to each other.” And I was just really inspired by the move from one to the other, and what it might take for us as educators as schools, higher ed and K to 12 and pre K as well, to embrace this shift as a challenge to move from begrudgingly giving people access and being grumpy about it to creating opportunities for collective joy.

Winnie: Yeah,I think I like that a lot. Because you have to be creative to do that. Right? If you yourself, don’t identify as a person with a disability or disabled, you might not know what people need. And if you want to include everybody, then you actually have to care about them as a human being before any of the other stuff. So I’ll say for example, with my students in my classes, I had quite a few students who had disabilities and had accommodations, and they were kind of shy to share what they needed with me. But on the first day, I say, Well, you know, consider what we’re talking about, it’s important to me that you feel you have access to, to, you know, the readings, to watch films, all that stuff. So if something’s not working, you have to tell me so that we can, we can make it more inclusive.

Jeanie: Right, so what I’m hearing from you, Dr. Looby, is that we need to be informed by others what they need and embrace that information, moving it from, I guess I have to ask you what you need to make this work from you, to like, I really need you to help me help you learn.

Winnie: Exactly.

Jeanie: And I think about K to 12 schools I can probably even place myself back when I was a school librarian and thinking, Oh, we’re going to go on this field trip, and then realizing it’s not going to be accessible to the kid who has mobility issues, say, and then instead of begrudgingly say, well, I guess I can’t do that field trip; finding ways to create this collective joy, and how do we make sure that everybody is able to have fun?

Winnie: Right, right, exactly. I think an important part of that, too, is the modeling that you’d be doing for that student and the other ones. So say, that student, you know, over the course of their lifetime, they can take in a lot of negative messages, whether that was an educators intention or not, they might feel like they’re too much trouble, or they’re not being included because of their disability. So it’s modeling for that student that yes, you’re important part of the class, and also for their peers, and that this is how you work with people and you include them, you don’t just say, Well, today, you’re just going to watch a movie at class in somebody else’s classroom, but more we care that you’re here.

Jeanie: That’s a beautiful thing to think about the modeling not just for the student with a disability, but also for the rest of the class about what it means to be a community, what it means to take care of each other. So the other thing that our author really gets at that I found really interesting is this idea that, that when the disability rights movement started it really invisible, invisible ized people who were I’m actually going to read her words, because she says it so well.

The Disability Rights Movement simultaneously invisiblized the lives of peoples who live at intersection junctures of oppression, disabled people of color, immigrants with disabilities, queers with disabilities, trans and gender-nonconforming people with disabilities, people with disabilities are who are houseless.

And she asked us to notice that ableism is intertwined with white supremacy and colonialism. And I’m gonna just confess here that I’ve been doing a lot of work over many years to think about my privilege, but ableism is something I’ve been able to ignore for a really long time. It’s something I’ve really recently been thinking, been considering is where ableism shows up in me and in my life. And so I really appreciated the way she sees these as intertwined systems. And I wondered if you had any thoughts on that?

Winnie: Yeah, yeah. I would say it gets me thinking about what do we consider normal, right? In our, in our broad culture, what do we call normal, we turn on the television, what’s a normal family? What’s a normal person look like? Right. And so I talk about race in this way too that if the only message you’re taking in is one kind of person, or people, and that leaves out a lot of other people. And so questioning the things that you’re taking in and the things that you’re assuming, I suppose. And I would say too that, it’s important to kind of take the shame away from that. Because without that input without somebody consciously saying to you in school, this is what ableism is, right? Or unless you’re, you know, before now, if you didn’t really feel the need to actively seek it out, of course, you wouldn’t know. Right? So the idea is that, you know, it comes to your consciousness, and then you’re aware of it. And then you’re also kind of, to me, it kind of opened up the door to lots of other things I hadn’t thought about before. That the analogy I can think of is, you know, the Matrix movie, where there’s a blue pill and a red pill or something like that. And the guy says, you can take this pill and learn what the world is really like. Or you can take this one and just stay with the way it is, right? And so I feel like once I’ve been exposed to oppression of any kind of other people, it’s opening myself up to understanding other people, rather than just staying kind of where I’m comfortable.

Jeanie: It makes me think about, you know, an increasingly problematic thing about our society is how segregated we are for people, unlike ourselves. Can we see that politically? Right, we see that in terms of racial segregation, we see that in terms of communities where there are lots of queer folks and communities where there aren’t. And then we also see that in terms of ability, right, that because of the way our societies are organized, I don’t currently have a friend in a wheelchair. I do have a friend with mobility issues, who considers themselves disabled. But I have to really seek out perspectives of people who are not able bodied who are not like me, and our world makes it harder and harder to do that.

Winnie: Yeah, I would say, well, mass or mass culture does, right. Our movies that are blockbusters, the ones that feature disabled people are always people who were kind of helped by somebody able bodied rather than having their own agency, right. I think it’s, I don’t think in and of itself, it’s a bad thing to seek things out, you know, to listen for, like, I learned so much in reading this book. I actually got it when I went to the Disability Intersectionality Summit in 2018. First time I went, and Leah was a speaker there, she actually her book had just come out. And she was reading a chapter from it. And just being in that talk, and in that environment, I thought, people can actually make the world more accessible if they really want to, I mean, I hadn’t seen such accessibility in my entire life. I mean, there were like these, these great badges where you could choose a color green, yellow, or red, green meant you were open to having random conversations with people. Red meant, please don’t talk to me. Yellow meant, maybe depends, right? So you’re respecting a person’s kind of social anxiety in that moment, there were pins that say, you know, here are my pronouns, you wouldn’t have to necessarily announce it. Here it is on my my chest. There were there were live captions, which I’d never seen before where in that moment, somebody’s typing in a large screen. what’s being said, there was somebody who actually opened up the event, acknowledging that the college that we were at, we’re at MIT, that it had been placed on ancestral lands, right? So owing, you know, giving respect to that piece. I mean, all of these things had been thought through very purposefully, very carefully. And there was even like a room where, you know, if you were completely overwhelmed with everybody, you can go and draw and have quiet time, right? I mean, just, they thought of everything. And I was really, I thought, why can’t everything be like that? It’s not that hard. Really thought about, it’s not that hard.

Jeanie: Well, so two things come up for me is one is I’m probably just thinking about using myself as an example again, right? Like, I have lots of friends of color. I have lots of friends who are different than me in different ways. But maybe I’m assuming I’m making assumptions about who they are. And and our world makes it hard sometimes for people to share their disability or to write like without making it complicated, because if, for example, if I had a disability, I might not want to share it, because I don’t want people to feel sorry for me or to pity me or to feel like they had to do things for me or to assume I don’t have agency. Yeah, that those stereotypes themselves get in the way. And that stereotypes I hold that everybody’s like me also gets in the way.

Winnie: Yeah,yeah, I think well, for myself, my own experience, I mean, I’m disabled. I use a chair sometimes, sometimes not. But I do catch myself in these ableist moments where I’ve internalized a lot of negative messaging, to say, if I want to be seen as competent at my work, I can’t share that, you know, I feel sick today. Or if I want to be seen as a strong and not lazy person, I have to leave my chair in the car and exhaust myself walking around the grocery store. I mean, you, you, you internalize a lot of messaging, whether people mean it or not. You don’t want to be treated differently. You don’t want people to kind of talk down to you because they think somehow that’s helpful. I don’t know. So yeah, it makes it it’s hard to feel like you can share who you are with the broader public. But then I’ve also found that on those days when I’m feeling brave, and I just don’t care what other people think those are the best days when I can just kind of let that go, and just do what I need to do without thinking about it.

Jeanie: Hmm, I really appreciate that. Thank you so much for sharing your personal experience in that way. Do you have advice for someone like me, we’re gonna get back to the book, do you have advice besides reading this book for someone like me, who’s really working their edges around their own ableism and trying to be to learn more.

Winnie: I would say reading personal narratives. So things that people have written or expressed about themselves, performances, whatever it is, and there’s lots of that out there, where they talk about their life’s path. And then you can see the great variety in what people have been through, you know, it could be a lot of intersectionality there with like, you know, socio economics, race, where they lived, language, you can see kind of the huge variety in what the disability experience can look like. And so then, for myself, at least, the more I read, the more curious I am about other people. And the less I assume that I know anything about them, which also is could be scary and intimidating. And maybe you feel like you’re gonna make a mistake. At the same time making those mistakes is, you know, like Leah talks about real Disability Justice is messy. It’s not like everything goes just so.

Jeanie: Yes, I love that section of the book. And what you’re making me think about, is for me, especially, but I think for a lot of people reading is a real act of empathy, and reading, #OwnVoices stories by people with disabilities is really helpful to building empathy and understanding about what the world’s like for someone who’s different than you. It creates what routines into what Bishop calls a window into somebody else’s experience or even a sliding glass door where you can really have under the answers step into their experience.

Winnie: Yeah, I found that the stories, people’s personal stories are what sticks with me when I try to think about, what am I going to talk about around disability injustice and inequality, I think about the individual people that I’ve met or read about.

Jeanie: Yeah, well, the other thing that Leah shares our author, Leah shares is this acknowledgement that the gains made in disability justice have been largely on the shoulders on the through the work of, of multiply-marginalized disabled people. So queer, black and brown, people with disabilities have really led the way. And it made me think about what that might look look like in our educational institutions. And it reminded me of a say that saying nothing about us without us is for us about being not doing for but being in solidarity with I guess my question, if I can formulate one, that is what does that look like in an educational institutions? What does that look like for people when they want to engage? We’re gonna get to the messiness of disability justice, but what does it look like to be shoulder to shoulder with instead of trying to make change for?

Winnie: I think, for me, it starts with respecting the agency of that other person. Seeing them as you know, having a complete other life that has nothing to do with me. And that my work as an ally would be to not stand in the way, you know, not speak for anybody not do anything for them, but offer myself as somebody who is there if they’re needed, right? I can be a gatekeeper in a positive way where, for example, of the last couple years of my job I’ve a lot of, I’ve gotten a lot of cold calls and emails from folks who are looking to work in this field. And those messages have been coming from other bipoc folks who are disabled. And I thought, wow, that means that I have a really important role in playing right here. Like even if I can’t directly do something for them or open a door for them, that they see me as somebody who could possibly be somebody they could talk to, about, you know, their future career. or goals or anything like that is a really powerful, important kind of role that I can play. And so I think, you know, teachers, in my experience with I have four kids, and three of them have disabilities. And so my kids, when they had the most successful time they had in school was when their classroom teacher, really respected who they were as people. And the child, my, my child felt that respect, really, I mean, it wasn’t like, if they really felt that the person cared about what was happening for them.

Jeanie: It wasn’t grudgingly given.

Winnie: Right, right. And kids can tell when you’re faking it. I mean, you’re trying to just be nice, and you’re not genuinely caring about how they’re feeling in that moment. So I think like listening to parents, especially parents, from marginalized groups, about, you know, they’re the experts on their own child, right. And as that child grows up, they’re going to need to learn how to advocate for themselves. And so encouraging that, you know, helping them to pull that out and say, This is what I need. I need help. I think a lot of messages kids get in school is that they shouldn’t need to ask for help.

Jeanie: I have so many follow up questions. But I think just returning to the book, you reminded me of a section of the book, where Leah talks about asset framing, versus deficit deficit framing. And, you know, this is this is a concept that crosses beyond ability and disability, Gloria Ladson, Billings, has told us for a long time that one of the most powerful things we can do for our learners, is to see them with an appreciative lens to see their strengths and skills and not focus just on deficits and struggles. And we know that’s a huge lever for equity, it’s a huge part of being culturally responsive in the classroom. And I really, still hear students with disabilities discussed with a deficit lens a lot. And, and the author writes, “able-bodied people are shameless about really not getting it that disabled people could know things that the abled don’t, that we have our own cultures, histories and skills, that there might be something that they could learn from us. But we do and we are.” And what you just said about your children’s experience in the classroom and your own experience as a scholar, made me think about the shift towards an appreciative lens for people with disabilities. And I wondered if you had any insights to share with us about how that happens, or what that looks like?

Winnie: Well, again, it’s it’s seeing the whole person, right? That I just had a conversation with somebody the other day about how, in one way or another, you could have an impairment, right, like needing glasses means that my eyesight is imperfect. If you look at it that way, everybody has a little bit of something that isn’t perfect, right? There is no perfect. An impairment becomes a disability when the environment is not there to support you. And what you want to do, or what you need to do, right, there’s not something inherently wrong with the person because they have a disability, there’s something wrong in the environment, in the social attitudes that they have to absorb and kind of do something with.

Jeanie: Some friends recently recommended a podcast that I listened to. And I’m not going to remember the person’s name, but I’ll put a link in the transcript. It was an On Being podcast and it was about asset framing. And the idea of asset framing really was what this person’s aspiration is? And what’s the obstacle to that? So instead of seeing them as the obstacle, what are the obstacles or them as the problem? What’s the thing they want to accomplish? And what’s the thing getting in the way of that? And so that removes the problem from the person to the environment, just like you’re saying, but there’s this other side of it, too, which is that there are things we can learn really big things we can learn from people with disabilities because of their experience of the world. So it’s not just that we don’t see them as a deficit, but also that we see their assets and their strengths and the things that they can teach us. Do you have examples? Do you have ways people might think about what they can learn the what the author calls the cultures and histories and skills and the ways that we might tap into that and open ourselves up to learning from people with disabilities?

Winnie: Well, one way I guess, is to I know, a state organization the Vermont Center for Independent Living. They’ve had public forums around different topics. And so one might be, you know, health care access, like something, something like that. And so inviting people with disabilities to come and share. This is what’s happening for me, this is what I’ve had to do to work, work my way around that. And it can be so gosh, it’s just, it’s hard to describe, especially with like, state, institutional things, I think she mentioned, like, social security and disability insurance and all that kind of stuff. Disabled folks have a lot of that in common. And, again, listening to people and their own personal experiences, I mean, just just really paying attention, not just saying, oh, you know, that person’s just complaining, or, Oh, they’re, you know, hypochondriac or, Oh, it can’t be that bad. You know, like, I think people of color have heard hear that a lot. Very similar messaging. I think it has to be, there has to be a willingness to realize that you don’t know everything. I think teachers are hesitant to say when they don’t know, or they’re not sure, or they made a mistake. I think you can start there.

Jeanie: I really appreciate that. I think for me, one of the tension points is–so I’m going to use Outright Vermont as an example. One of the programs that Outright Vermont offers in schools that I think is really powerful as they have queer kids come and sit on a panel and answer questions and talk about their experience in schools. They used to, I imagine they still do, but when I was in school, they, you know, we have in common it was really powerful for people. The tension for me is about like, it’s not really their job to educate me. And so how do we learn from and with without expecting people with disabilities or people of color queer folks to do the work for us? So, there’s a real tension for me about like being open and I think that’s why your suggestion earlier about seeking out personal narratives that people have written, seeking, seeking out books like this one is really helpful, right? Because that’s out there. And I’m not asking people to do additional labor. And so I guess I’m just wondering how do you grapple with that tension, the both and of like, I want to learn from you, and I don’t want you to have to do a ton of work for me to learn like I should be doing the work.

Winnie: Yeah,I think well, one thing I learned through my scholarship a few years ago, I did some research around culturally responsive research, like how you might be a researcher, academic who wants to do research in a community, that community might be disabled, BIPOC, intersectional, lots of different kinds of ways. How do you do that in a way that’s respectful and they don’t feel exploited? Right? Think about what’s in it for them. Right? Those kids that come on to a panel most likely wanted to because they want to practice speaking up for themselves to practice self advocacy to practice leadership. Right? So saying, Okay, if I want to learn something specific from this specific person, I have to think about, well, what is what’s in it for them? Right? What is that, that I really want? Is it that I’m being nosy and just want to know details about their lives? Or is it do I want this kind of mutual exchange of information that benefits us both equally in some kind of way?

Jeanie: That’s helpful. And it reminds me of a section of but we are jumping, by the way listeners all over this book all over different sections of this book. But one of the sections of this book that really, I think was most interesting to me, was about, trying to find this specific quote, was about mutual aid. And so, in one of the chapters, the author talks about this voluntary reciprocal exchange of resources and services for mutual benefit, she goes on to say mutual aid as opposed to charity does not connote moral superiority of the giver over the receiver. White people didn’t invent the concept of mutual aid. Many pre colonial black, indigenous and brown communities have complex complex webs of exchanges of care, and this idea that I think so Often, in our society, we have this like white savior notion, or what you’re talking about is like this, when you were saying earlier that their characters with disabilities in movie say, and so often it’s about this able bodied person who comes to the rescue, right? And it totally means that in that storyline, they’re devoid of agency, right? The person with a disability is devoid of agency. And so this idea of mutual aid, is more than a nod is sort of honoring that we need each other. And that in communities, we take care of each other. And I wondered if you had thought about what mutual aid might look like in an educational institution in a school in a community? Yeah, or if you have any examples?

Winnie: Yeah, I can think of one example. I remember when I first started my doc program, there was an article we read about schools, public schools in say, pre-desegregation, right. So the article was saying that Neighborhoods and Schools kind of lost something with desegregation when kids had to be bused to different schools, because before then the school had been this hub of community, right? The teachers might live right down the street, and parents would know each other. The kids knew that there were adults around them that cared about their well being. I think that there is a deep desire for a lot of people to feel more connection than they do. In general, and I think if we can cultivate that in earlier ages in school, and to say, to kids, it’s okay to need other people to say to parents, that it’s okay to ask for what you need or to be, you know, demand what you need from the teachers and the principal and whoever it is, and that it’s okay for teachers to make mistakes, you know, it’s okay, for, it’s okay for that struggle to happen. Because without that, that means that we’re not even trying.

Jeanie: Ireally appreciate that. And so it makes me think that this book made me think a lot about rugged individualism and self sufficiency, it made me think that that’s something like we value as American society, right, rugged individualism and self sufficiency are sort of baked into how we think we’re supposed to be in order to be successful. And it gets in the way of asking for help from others. And it kind of creates a culture where you’re ashamed to ask for help. And recently, two things happened in my own life, that’s, that helped me that this book spurred new thinking about and one is that, um, some friends had a complicated pregnancy and a baby that needed some NICU support and, you know, they were so it was such a joy for me and some other friends to cook for them and provide some self care items, you know, it’s COVID. So a baby shower wasn’t really an option, but we like sort of threw together this, like, Here, take this and make yourself a baby shower. And my job was to provide them with meals for the freezer. That was my role I like to cook and, and they were so like, totally lovely in their, like, Oh, this is too much, we so appreciate it. And I was like, really, it’s a joy to do it. Like there’s reciprocity in this that I felt real joy in giving. So that’s one example. And then just the other day, I got an email from somebody saying, Hey, I’m gonna have surgery, and I’m gonna need some meals. And I’m gonna need some people to take me to appointments, and I’m calling on you as a group of friends. And here’s my meal train. It’s the first time I’ve ever received a meal train from somebody who set it up for themselves. And I was like, that is the baddest thing I’ve ever experienced. Like that is the coolest, like most empowered thing, that you set up a meal train for yourself, you’re my hero. And just thinking about that. The power in saying, I am not a rugged individual, I’m not self sufficient. I need people who care about me. I’m willing to ask for your help and receive it. And I know that I’m giving you a gift as well. I know that you want also to do something to help me. And that, that that reciprocity is a gift for you. And I just, I don’t know, I can’t stop thinking about how that’s the bravest thing that I’ve seen somebody do in a long time. And it made me wonder what would it look like if we like kicked self sufficiency and rugged individualism to the curb in schools and focused on creating communities of care where we can ask for and give the things we needed or that others needed. I was really wordy. Thank you for bearing with me. Dr. Looby. Any thoughts on that?

Winnie: Yeah, I think, Well, for me, the great place to start was to see that they call it the myth of meritocracy, right that we pull ourselves up by our bootstraps to be successful. And that’s not the case at all. Right? That that was set up by people who wanted you to work for no money, and work yourself into the ground and leave the workforce if you got hurt on the job, people who don’t care about you, right? So if you think about that, thinking, it doesn’t serve anybody except for people who make a lot of money off of what you’re doing.

Jeanie: Right? And it hides, it’s like hides all the privilege that people call on when they so-called lift themselves up by their bootstraps.

Winnie: Exactly, you know, this person that’s a friend of my uncle gave me an internship someplace, right, or, you know, there were these, oh, God I could get into a whole thing about, like, financially for, for folks of color, starting off with how there’s generational wealth that we don’t have, a lot of our communities do not have. And so when you say you can afford to buy a house, you’re buying a house with money that your great grandpa had saved, My great grandpa worked, you know, at a railroad, he didn’t have that kind of money to give me. So thinking, pulling apart all those assumptions that we make about how the world is supposed to work, I think kind of frees us up to be more generous and compassionate.

Jeanie: Well, and so when I read this and started thinking about this, I was thinking, oh, one of the like, paradigm shifts, or Aha I had is that disability justice, I’m almost ashamed to say this out loud, but I’m gonna be really vulnerable and say that that disability justice isn’t an extra an add on, it might be the very way to pull us towards a more liberatory future it might be. And it makes me think of to Dr. Bettina Love, who says, If you really want to work towards liberation, listen to queer black women. Right. And so this like sort of adds, like, people furthest from justice are actually the people who can help us see a clear path to justice.

Winnie: I like that. Yeah, I think I think we made some great points about, you know, the ingenuity that you have to have to be able to kind of survive in the world the way that it is, when you have multiple marginalized identities. The, I don’t want to say grit, that’s not right, the word but the, I guess, being comfortable with feeling out of place. And pushing past that anyway, like being in my doc program. I was the only person that looked like me in my cohort. And it was really uncomfortable that first semester, but then I also thought, if I can get to the finish line, I can open up the door for so many other people, right? Even if they just see me on the website, and my picture that I went through the program that will give somebody kind of a boost to feel like that’s that’s for them as well.

Jeanie: Well, and I know you’re making a difference, because a friend of mine is black, and is taking a class with you or took a class with you. And you are the first black person he had had a class with in our doc program.

Winnie: Oh, wow. Yeah.

Jeanie: And that’s huge for him. Right? That would be huge for me, too. I unfortunately, have not yet taken a class with you, Dr. Looby, but maybe in the future. So I think you’re right about that. But it also makes me think, Okay, I’m gonna take this to Vermont schools. But it makes me think about interlocking systems of oppression of which ableism is a part. And I think that often is really easy in our society to pit oppressed groups against each other. And I’m going to give you an example. In Vermont, for example, when we’re talking about equity, which I talk about schools with all the time, I will often hear the this this comment, we should be focusing on poor kids because those really are the most marginalized kids in Vermont schools. That’s the comment I’ll hear. That’s not my words. Those are a paraphrase of the words I hear. And that really gets my dander up. Because it’s a way of glossing over or ignoring racism, sexism, homophobia, heteronormativity and ableism and the intersections of them that just by focusing on class, we’re ignoring all these things that poor up poor kids might also be experiencing. And and that’s mean that works to maintain power and privilege, right? Like when we pull them apart and say we’re just gonna focus on class. We’re actually not even alleviating the problems of classism, because they’re so interlocked and intersecting.

Winnie: Right. Right. Right. I always, I always wonder why folks put it that way. Right. Is it coming from their own discomfort? I think about we call it the dog whistles you hear on in the media about when you say diversity, you mean black people? When you say urban, you mean, you know, these coded words that everybody in that circle would know what you mean, instead of just saying what you mean? I think that’s where it comes from, you know, this individual kind of, well, if I say that it’s not on the table, that it’s not, and we don’t have to look at it. Right, that I’m the leader here. And I’m saying that this thing is the most important thing, these other things don’t matter. Because I don’t want to look. I mean, nobody would ever say it that way. But that’s actually what’s going on, right that like, in my, I worked as a para long, long time ago. And I noticed the dynamics in school were that the principal wasn’t in charge. It was the teachers who had been there the longest who were in charge, right? They set the tone for the culture of the school. But nobody wants to talk about that openly. But like you kind of have to pull apart. Why is it like that? Who said it‘s like that? Who set the rules in that way and why?

Jeanie: You’ve got me now visualizing this image of a knotted up ball of string. And if we just untangle the knot, that’s about classism, we still have a bunch of knots, right. And often before we get even get to that knot, they’re a bunch of knots we have to go through. And so seeing it as a an interlocking system of knots, as opposed to like, Oh, if we just focus on classism, and people often say, Well, you know, Dr. King, at the end of his life was only focused on classism when I was like, only? like, you know, like, I think it’s a little more complicated than that. Right? And so I think,

Winnie: capitalism,too, I think.

Jeanie: Yes, yes, yes. I’m seeing the intersections of these things. Isn’t extra, it is, it is the thing, right? It’s the it’s the way forward. And I think disability justice movements, as Leah points out, have been really led by people who are multiple marginalized in a ways that see those intersections that experience the intersections of not just ableist systems, but also classist, homophobic, heteronormative, sexist and racist systems. And so I have a clearer sense of how the things all fit together just based on our experience. That’s what I read from Leah.

Winnie: Yeah, yeah, I think so too. I think so too. I had um, I thought also, I’m still thinking about this person that thinks class is the only thing I think, also that folks want the shortcut, right to say, this will get done faster if we just look at one thing. So let’s just talk about that one thing right now. Or I think true, transformative change doesn’t work like that. It has to be this kind of constant chipping away. Constant spreading awareness, constant self inquiry. I mean, it’s not something you just kind of get done with and then everybody’s fine. It has to be purposeful. And connected. It just it just has to.

Jeanie: Yeah. But there’s a scholar I really love named Vanessa Andreotti, she’s from Canada. And she uses this thing called the Heads Up framework. I can’t tell you what each of them stands for, ‘H’ is hegemony. The one that always sticks with me the most is the easy solutions, right? And easy solutions, which I think we all want, because we want to solve the problem, right? Is actually a red herring, right? Like, they’re often a sign that we’re not actually dealing with a real problem. An easy solution is often not the is almost always not the answer. And as you alluded to earlier, and as we talk a lot, working towards justice is a messy, messy system. It’s a messy process because these aren’t simple problems that we’re solving, right. And they’re also not only systemic, but they’re also the way that the systems we live in have shaped who we are and how we show up how we are in the world. And I was listening recently to a Hidden Brain episode, I’ll link to in the transcript about what happens when change decision making from ethics, like our moral decision making to financial, to sort of this, which a lot of our decision making in our current capitalist world is really financial. And it shifts the part of the brain it works. And we make decisions that don’t help us make better decisions. And in fact, so often, the example they use is if an after-school program charges you, if you get paid, charges you a fine if you’re late picking up your kids, and they set for a lot of people, they’re just like more people were late because they felt like they could just pay the fine. So it had the opposite impact.

And I think a lot about the decisions we want kids to make at school, we turn to this sort of financial decision-making, right like through a token economy. And we say, well, you get a reward if you do this thing, or you’ll get a punishment. If you do this thing. Instead of saying this is the right thing to do. This is the way we take care of each other, let’s be our best selves. And so gosh, I just went on a long tangent, but my point was, I did have one doctor, maybe I did. I guess my point was that these easy solutions often shift us into our worst selves, right, and we want this quick way of fixing something wrong. Really what we need to do is grapple with whom do we want to be? How do we want to be in this world? What kind of moral-ethical person how do we want to show up? And I think you keep reminding me that there’s no single easy pass through all this injustice, we just have to wade in and get messy. Thank you for bearing with me and that nonsense I just spoke.

Winnie: oh, that was great. That was great. That was great. I’m really enjoying how you’ve been processing all of this really, I usually process through my own personal experience, it’s how it kind of lives in me. So if I’ve personally experienced it, or somebody close to me has, then that’s the thing that I’m going to anchor myself to. I find that, you know, in higher education, say, I just went through this whole process of getting my contract renewed as a lecturer. And so in that process, you’re supposed to show all the things that you’ve been doing with your time, in the last four years, you know, like the ideal is to have, you know, when you get out of PhD school, the idea is to find that tenure track job, right? tenure track, meaning that you prove yourself over seven years, then you have this job for the rest of your life, right? They’re not really concerned about what kind of work you do after that. Right, you’re just gonna, you’re just gonna, you know, work really hard to get that piece of cheese or whatever it is. And what I’ve found in the last four or five years is that I don’t really want that cheese, I want to actually get stuff done. Right. And actually getting stuff done means that I have to let go of a lot of other extraneous stuff. So for me, it’s like labels, it’s it’s money. It’s all those things, right?

Jeanie: Figuring out what really matters to you.

Winnie: Yeah

Jeanie: And that often goes against I mean, tenure track really is a it’s part of that meritocracy. It’s part of a capitalist system. It’s like credentialing, right? Like, who did you publish enough to get tenure? And so deciding that how you want to be in the world matters more, the things you want to accomplish matter more.

Winnie: Right now, right now, I’m actually working on a book that is from my dissertation. And I decided that like, you know, I spent four years learning all these $20 words. Now I’m going to unlearn it so that this book can actually be read by regular people.

Jeanie: What’s your book about?

Winnie: Oh, I did this great action research project around self perception, self esteem, social emotional learning in the arts, and how creating inclusive learning environments for students kind of helps kid peer relationships. It supports You know, the learning of kids with disabilities where they can show what they know in lots of different kinds of ways, not just by taking tests. And then it also enriches the whole school culture to become more of a caring, open minded, flexible kind of culture. And so I talked about Well, so far, I’ve been writing it for like three years now. I spend a lot of time trying to make the research relevant to real life. To why is it important to understand how meritocracy works? Why is it important to understand why it’s important to engage with families around their own children?

Jeanie: Dr. Looby, your book feels like one I really have to read and want to read and can’t wait to read. I hope that when it’s published, you’ll come back and talk to us about it on the podcast.

Winnie: Absolutely. Absolutely. I’m hoping to be done with it before another couple of years.

Jeanie: Well, we don’t wait patiently until then. But the world needs your book, I think. Yeah. What are the things that when you when you said the things we need to understand, like you said meritocracy, and why we need to understand these things in order to do a better job in schools. It made me think about some of the things that were really hard to read about in Leah’s book. And one of those was this history of ugly laws in the United States. It’s really painful. And so I’m just going to quote her, she says, “the ugly laws on the books in the United States, from the mid 1700s, to the 1970s 1970s, stated that many disabled people were too ugly to be in public, and legally prevented disabled people from being able to take up space in public. These laws were part of a system that locked up or criminalized all kinds of undesirable people, indigenous folks, poor folks, people of color, queer folks, and disabled folks.” And so it made me think about all these other laws that we don’t often talk about, but that have lasting implications in our world. So it made me think about eugenics, for example, which in Vermont, as well as elsewhere, sterilized, and institutionalized people considered delinquent or defective, many of them poor, indigenous, or disabled. And it made me think about other kinds of laws like redlining, that, you know, profited or benefited privileged white folks, while denying those benefits or privileges to people of color who maybe also fought in wars or right, or who were looking to buy homes, right, the same American dream. And I think about and I’m sure we can name countless other laws and statutes that play out in this way, that means some people have privileges, or are not allowed to have privileges. In this case, the privilege was being allowed to be in public taking up space in public, and that folks where it made people who able bodied people uncomfortable. And so we created laws for that. And it was just horrifying to me. And I think those things still play out in schools, right, like those the ramifications of that still plays out in systems of education in the way students with disabilities are treated. And I wondered if you had thoughts on that?

Winnie: Yeah, yeah, the connection I’m making with school is, I remember not ever seeing a child with disability in my school, in the 70s. I know that where they are now I know that they were there. But then I had no idea. And I wonder, I get down to the real feeling behind why that’s necessary. I think, even though disability has been, you know, one in four people in the world, has a disability. Right. There’s plenty of people that we know that won’t ever talk about their disability, because of the stigma involved. And I think I think the reasoning behind that, that shutting away or that pushing away is this kind of fear that life is unpredictable. That, you know, you can’t control everything, you can’t have rules for everything. You can’t. You can’t control your mortality. You know, I don’t think people like that. Right. They want to know that the world is exactly the way that it was when they woke, you know, went to bed last night. They don’t want change, I think, I mean, might be controversial to say it but I think that’s partly why folks are so, so eager to get back to normal with COVID. Right? Even though statistics are showing us that we’re not done with it yet. People really really, really don’t want to wear a mask like like that’s that’s a really small, really small thing that you have to give up to benefit other people. It just to me it kind of gets at this fear about what you can’t control what you can’t fix. You know, what’s unpredictable about just the way the world works. I think that’s kind of I can’t say it’s good or bad. I just think it’s a human tendency to, to say, I’m more comfortable with things that are are knowable that I understand that look like me that sound like me. And anything other than that really throws me off.

Jeanie: As you spoke, our listeners can’t see this because they’re listening, but you put air quotes around normal. Oh, yeah. I really appreciate that. Because I think what you’re reminding us is that with those air quotes, what I read from that, and I’ll ask you if I got it right, is that normal is a myth that normal doesn’t exist that normal. In many ways, I took the next leap and thought, well, normal is what we used to keep the status quo as it is, and the status quo doesn’t serve all people.

Winnie: Exactly. Exactly.

Jeanie: And I did a podcast with my friend Emily Gilmore about the End of Average which really describes why this norm reference to this norm normal really is, is related to averages, right? Doesn’t serve any of us, none of us are really normal, right? And so that this notion of normal, and this privileging of this notion of normal, is problematic just because it doesn’t exist, it’s reusing, right? It’s using statistics to describe people, and that just doesn’t work. There’s a fallacy. It’s very hard, it’s that.

Winnie: Well, it’s also it’s also defining this kind of mythical ideal, right? That if you have a normal body, whatever that is, that means that you look a certain way. You feel a certain way about yourself, like our I think our like beauty industry is all around “I want to be that ideal. “ But it doesn’t exist, right? It’s keeping people’s kind of aspirations to have the thing up. So like, say, what do you call it? My grandparents used to call it keeping up with the Joneses. Where are you know, you have a neighbor that gets a new pool, though, you have to have a pool they get a new car, you have to have a car? What is that all based on? And who is that serving other than the people who you’re buying from? Right?

Jeanie: Yeah, our our feelings of inadequacy really do serve people who want to sell us something, right? We joke about that at my house. I’m like, why there are certain times in my life or certain days, certain periods of exhaustion or frustration where some email advertisement really can get me and I have to step back and say, oh, I need that thing. I just feel bad about myself at the moment. And that thing, that shiny thing is, is a way to that I think will make me feel better. But it doesn’t really, right.

Oh, yes. And one of the things that Leah pointed out in the book is that it’s really short sighted of us not to be looking for disability justice, because so many of us as we age will experience some kind of disability. That by the way, self interest isn’t the only reason that we should engage in disability justice. But she does point out that like, and you sort of allude to that too that. It’s our our lack of desire for change that keeps us where we are, and our lack of understanding that we could face as our people we love people in our own families in our own lives can face disability, it’s really short sighted of us not to not to clear the way so that all people can take up space and be valued and and be acknowledged and identified with their strengths. There’s one more concept I want to talk about in this book before we move to close. And that’s this idea of care webs. Would you do you think you could define care webs?

Winnie: TThe way I understood it was that you I love how Leah talks about it, where it’s it’s people with disabilities who are all supporting each other, right and pulling in allies where they’re necessary. And not so much doing things for each other, but really just caring about what’s happening with somebody else that like she talks about how isolating it could be, to have a disability, right? That if you feel like you can’t talk about it at work, or you know, you’re feeling, you know, vulnerable around how you’re treated within your family or anything like that, that it’s important to have these other people who understand at least somewhat of what your life is like, to kind of alleviate that isolation. So I think like a great benefit is the actual, like, somebody’s going to help me cook and do my laundry. But I think for me, the important part would be that that social connection piece.

Jeanie: I really appreciate that. And there’s a page in this book, and I’ll put an image of this in the transcript that says questions to ask yourself as you start a care web or collective and keep asking messy again, code word messy. And so it starts with these really practical things like what is the goal of your care web? Who needs care? And what kind, but it moves towards these other things? Like, how you how will you celebrate and make it fun? Or what’s your plan when conflict happens? Or, and this is one of my favorites. And I’ve talked about this in other places, not around disability, but are you building in ways for disabled folks to offer care instead of assuming that only able bodied people are carers? And I’ve talked about this with the book Piecing Me Together of who do we think gets to give and who gets to receive? And how do we create opportunities for everyone to give and receive, because we all have something to offer, and we all need each other? And so if we’re just one, otherwise, we fall into the charity model again, right? We fall into the white savior model, again of like, oh, look, I get to be the hero, as opposed to mutual aid model of we’re in this together. And we’re creating communities where there’s reciprocity, and where we take care of each other.

Winnie: Yeah, I would say the leadership piece is important. Where say, you’re an able bodied person who wants to do something with Disability Justice, well, it wouldn’t really start with what you think or what you feel. You know, you need to follow the lead of the folks who are most affected by this thing, right? It’s, I guess, for me, it feels like kind of obvious that that’s what you would do. I think, because it cares. I care about understanding people as individuals in their own path. And I spend a lot of time in self reflection, just because I feel very responsible to my students.

Jeanie: What I hear you saying is that we need to center relationships. And that those and the inference I’m making is that when we center relationships with individuals, we can use the knowing them and their voice and their experience to understand the problem with systems. Yeah, I hear you correctly, when that’s what?

Winnie: Yep, exactly, exactly. Yeah. There’s a section in her book, which talks about, was it emotional intelligence, where how folks with disabilities understand the idea of like, pushing past what your limits are, because there’s something that you want to do or need to do they understand that they understand that the difficult conversations you have to have with whatever bureaucratic office there is that has some kind of control over your life. They, they, they get it. So having those folks in your life is important to kind of keep keep your sanity to keep you kind of motivated to move forward.

Jeanie: So that touches on I guess there’s one thing I wanted to really point out from the book, and it’s this notion that of freedom dreaming, I’ve been thinking about freedom dreaming a lot. And I’ve been thinking about you know, Ibram X. Kendi and Jason Reynolds point out that racism was created via imagination, and it’s gonna take imagination and creativity to uncreate it or to fix it. And, and so Leah says “sick and disabled and neurodivergent folks aren’t supposed to dream, especially if we are queer and black or brown. We’re just supposed to be grateful that the normals let us live.” And it makes me think about what’s it look like to to, to center aspirations and dreams for All people. I guess that’s also the opposite of charity. Oh, look, we’re being nice to you, you get to survive, as opposed to like, what are your dreams for the world? And how can those dreams help inform my dreams for the world?

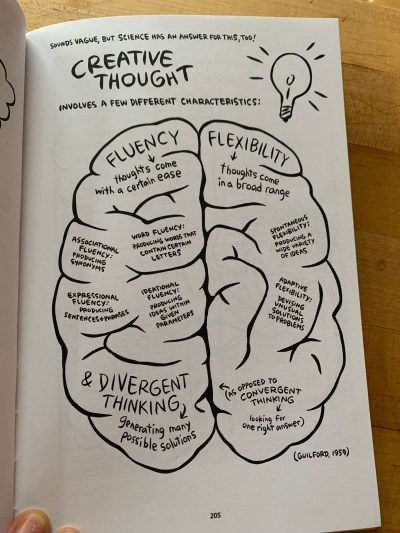

Winnie: Yeah, um, well, I have, I think I have kind of an analogy that relates. In my I teach a class on race and racism in the United States. And the first couple of weeks, we spend time thinking about our own identities before we talk about any history, any anything else. Who, what makes us who we are? Where do we grow up? What languages do we have? How important or not is religion? What’s our gender identity? All those things about ourselves, right? And then connecting that with do I or do I not understand how race and racism works? Why might that be? Oh, if I went to, you know, this affluent boarding school where there weren’t people of color, of course, I wouldn’t have learned very much, right? And so in that moment, you’re saying, Okay, I’m going to give up control that I know everything that I know anything about this thing, whatever it is, and then I’m going to take pleasure in having those conversations with people who have been through those things, right, taking away the shame and the the feeling of like, you know, I have to make up for what my grandpa did, right? Take away that and say, how do I learn about other people for who they are? How do I grow as myself? In what I’m learning? How do I keep learning, it’s not like, cultural competence is going to be this end goal. Because there isn’t really one, there’s always more to learn. I mean, I said, I learned so much from his book, things that I didn’t know before, you kind of have to be open to that. So creativity requires being able to say you don’t know, being vulnerable, thinking, you know, following the lead of other people who wouldn’t necessarily get the lead, usually, right? Being willing to kind of just up end the way you think things work. To make it something else, you can’t you can’t follow the same playbook, you have to completely throw it out the window and create a different one.

Jeanie: Oh, my gosh, that was so helpful. What you just said that such a like helpful way to wade into the mess. And although I have a gazillion other quotes and ideas from this book, my last question for you was going to be what advice do you have for teachers who want to, you know, join the Disability Justice fight, if you will, and celebration? The all the things that disability justice is, what steps do you have for them to wade into that mess a little bit to start to get messy around their thinking, and you just sort of nailed it with that, but I’ll leave it for you to add any other advice you have for teachers, for educators?

Winnie: Yeah, I would say beyond, you know, self reflection, right, and talking to people with disabilities talking to kids about what they want, right? What they need, talking to their families about their experiences. Beyond that. There’s tons of resources around, you know, Universal Design for Learning, where you’re going to learn about colors, there’s lots of different ways to do that, right? Through music through sound through tactilely, you know, not just reading, you can do lots of different things. So, for a teacher to kind of see that as a creative challenge, a positive creative challenge, where if I want every single person in my classroom, that I don’t know everything about them, right? If I want to have them feel included and want to come to school, what does my classroom have to look like?

Jeanie: I love that it reminds me of a phrase we sometimes use at the Tarrant Institute called planning for the margins like start, don’t start with the middle what most kids need, start with the margins and playing with them in mind. I’d love to embed some of your resources and ideas about universal design and other things into the transcript. Dr. Looby, thank you so much for taking time to talk to us. Thank you for bringing this book to my attention. I learned so much I have so much learning left to do. I just so appreciate this conversation with you. All all of the expertise you bring and I cannot wait to talk about your book with you.

Resources from Dr. Winnie Looby:

-

The Include! curriculum is about disability studies for K-12 students and was developed by the VT State Independent Living Council

- UDL Guidelines from CAST

- Learning for Justice

- The Disability and Change Symposium from the Institute on Disabilities

Winnie: Thank you, thank you. I really enjoyed this too.

Jeanie: Thank you.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y2PD4n7qyxw[/embedyt]

![What Shapes Your Identity? [Link to slideshow]](https://i0.wp.com/tiie.w3.uvm.edu/blog/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/IdentitySlides.jpg?resize=474%2C265&ssl=1)

Listeners: how do you talk to your students about the special love that exists between a woman and a Sasquatch? Or between an insect and a robot-powered building? And where and how do you determine which texts are appropriate to give to students?

Listeners: how do you talk to your students about the special love that exists between a woman and a Sasquatch? Or between an insect and a robot-powered building? And where and how do you determine which texts are appropriate to give to students?